It has been over two years since the 'clearance operations' of the Myanmar military forced hundreds of thousands of Rohingya from their homes across the border into neighbouring Bangladesh.

Human rights groups and the UN published myriad reports of mass rapes, killings, and torture on a terrifying scale. The consequential humanitarian crisis in Bangladesh remains a challenge for aid agencies, and survivors of the violence in Myanmar remain vulnerable to ongoing threats in the camps. The situation for the Rohingya still stuck in Myanmar is even worse.

But the international community failed to act on the genocidal acts perpetrated by the military. China and Russia have refused to allow the UN Security Council to hear a briefing on the situation in Myanmar, let alone refer the situation to the International Criminal Court where individual perpetrators could be charged with genocide.

China has longstanding geostrategic interests in Myanmar, including land access to the Bay of Bengal and the country's rich natural resources. Russia's interests are often in never letting the international community stand in the way of a state acting autonomously within its own borders.

Why Gambia?

Myanmar is not a member of the International Criminal Court, so without a referral from the Security Council the only charges that court can pursue relate to forced deportation of Rohingya to Bangladesh.

But before the International Criminal Court was even conceived, in the aftermath of the holocaust the international community agreed that genocide was a crime that was everyone's responsibility to prevent and punish.

It is this treaty, the Genocide Convention of 1948, that has allowed Africa's smallest continental country to take the government of Myanmar to the International Court of Justice for the genocide of the Rohingya.

The Gambia, a majority Muslim country, is bringing the case on behalf of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, but the campaign to bring the case has been led by their Minister for Justice, Abubacarr Tambadou who had previously worked on prosecutions for the Rwandan genocide.

When Vice-President Isatou Touray announced to the United Nations General Assembly they would be pursuing the case, she said The Gambia "is a small country with a big voice on matters of human rights on the continent and beyond" explaining that pursuing an ICJ case against the government of Myanmar would be a central pillar of this policy.

The Gambia is returning from a period of political turmoil. The new government has prioritised human rights policies domestically, across Africa and the world. Pursuing a case at the International Court of Justice is deeply connected to this priority and is an expression of good governance and support for international law.

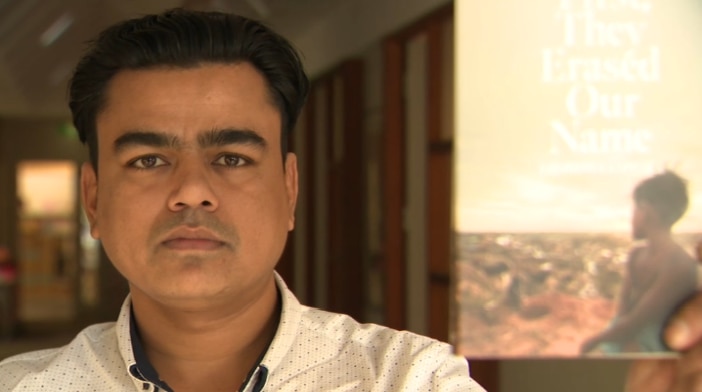

Upon hearing the news about the case, Refugee Council of Australia Ambassador and Rohingya refugee Habiburahman (Habib) said he was relieved.

"It is the first time member states of the United Nations are unitedly standing up against genocide of Rohingya ... I hope one day it will achieve justice for Rohingya people," he said.

There has been an advocacy effort for The Gambian case to be supported by non-Muslim countries as well. In particular, significant efforts were made to get the Canadian government to join the case. But no other country joined The Gambia as co-applicant.

What happens now?

A case before the International Court of Justice may take years to play out. But it can have some immediate benefits for Rohingya.

The Gambia has requested the court make provisional measures, which are orders of the court that are binding on the government of Myanmar, including the armed forces. The Gambia asked for such orders to be made to protect Rohingya from ongoing acts of genocide and prevent the destruction of evidence. The court can issue such orders in a matter of weeks.

Because the International Court of Justice is not a court that deals with individual accountability, but state responsibility, no one goes to jail at the end of a case.

What will it achieve?

The focus of this court is about settling a dispute between states about the implementation of a treaty. So, it doesn't have the same approach to victims as other courts. However, the court does have the capacity to award reparations.

The main benefit of such a case is that it recognises the collective harm, rather than just the individual harm of genocidal acts. Genocide is a crime intended to destroy an entire community. The entire Rohingya community has been affected, and a case before the International Court of Justice is the best way to account for that.

For Habib, this case gives some hope of a different future for Myanmar and the Rohingya.

"The military generals have never been prosecuted for their crimes, in the past or the present," he said.

"It is very important for the future that they are held accountable and they change their behaviour. This case will shape democracy and the rule of law in Myanmar."

No comments:

Post a Comment