In February, Myanmar's military, the Tatmadaw, took back the little power they had ceded to Aung San Suu Kyi's National League for Democracy (NLD). Since then, the world has watched in horror as Myanmar's authorities have suppressed popular resistance. So far, over 550 people have been killed and the scale of the crackdown is escalating.

Despite the brutality, the people of Myanmar are resisting, led by the country's labor movement and student activists. Mass meetings, strike committees, and widespread protests have given us a tantalizing glimpse of what a democratic Myanmar might look like.

Australian authorities have added their voices to the international condemnation of the crackdown, making it seem as if they have nothing to do with the Tatmadaw and its actions. But this could not be further from the truth. Just as Australia's rulers have supported repressive regimes in Sri Lanka, Indonesia, and elsewhere in the Asia-Pacific region, they are intimately involved with Myanmar's military ruling class.

Opening Myanmar for Business

In 2010, Myanmar's ruling junta released NLD leader Aung San Suu Kyi from house arrest after sixteen years of imprisonment. Her release appeared to symbolize a new era of power-sharing between the junta and the NLD. To many in the West, it was a landmark moment in Myanmar's transition towards democracy. In the Australian parliament, Josh Frydenberg called on Australia to aid this transition. This would involve, he suggested, "a policy of engagement with the Burmese hierarchy."

Before long, it became clear that Western praise for Myanmar's apparent transition to democracy was premature. Myanmar's constitution still enshrined the junta's power. For its part, after winning the 2015 elections, the NLD largely preserved the existing balance of power. For example, the NLD did little to challenge repressive laws or push for the release of imprisoned student activists.

Kyaw Ko Ko, former head of the All Burma Federation of Student Unions, has argued that the NLD's inaction while in office amounts to complicity:

If students and the people are still being oppressed by those who would rather use these laws than repeal them, then it is no better than what we went through under the military regime.

The NLD's attempts at reform were at best insufficient and at worst disingenuous. Aung San Suu Kyi's approach to government was profoundly authoritarian and in line with neoliberal economic principles. Suu Kyi consistently called for partnership with the generals. She and her party shunned democratic popular movements such as the mass protests by farmers for land rights in the face of new resource-extraction laws.

Profits from resource extraction in Myanmar have enriched military elites. In 2015, Global Witness revealed that the military and drug lords largely controlled Myanmar's $31 billion jade industry, with very little of its massive profits benefiting ordinary people.

"Engaging With the Hierarchy"

While all of this was going on, Australian businesses saw an opportunity to invest in Myanmar's mining industry. The junta's liberalization of trade opened the door. Around fifty Australian firms now operate in Myanmar, including ANZ Bank, BlueScope, and Woodside Energy.

Woodside alone has invested half a billion dollars through holding companies in Singapore. The Australian Trade and Investment Commission has supported these ventures, eagerly touting Myanmar's natural resource "endowments" and praising deregulation as a positive step while raising mild concerns about the rule of law.

In 2013, Australia's official "engagement with the Burmese hierarchy" broadened to include military assistance to the Tatmadaw. In 2014, Tony Abbott's Liberal government appointed Royal Australian Navy captain John Dudley as a resident military attaché in Rangoon. In 2015, Australia added Myanmar to the Defence Cooperation Program, under which Australian personnel trained Tatmadaw officers in UN peacekeeping methods.

In 2016, the Australian Federal Police signed a pact with the Myanmar Police Force — which is incorporated within the Tatmadaw — to boost operational coordination and "capacity building" in response to international crime. The Australian government justified this as a move that would advance democratization by promoting "professionalism and adherence to international laws." Andrew Selth of Griffith University and John Blaxland, a former military attaché to Thailand and Myanmar, have argued that a partnership between Australian personnel and Burmese officers would make for a more open-minded Tatmadaw leadership.

Burmese Australians were not so optimistic. Human rights activist Cheery Zahau sounded the alarm over continued abuses in Myanmar, noting that the Junta's respect for human rights was contracting, not increasing:

Although there are a lot of exciting reforms happening in Rangoon and in Naypyidaw, in ethnic areas it's not getting better. . . . In Kachin states, in Shan states we see a lot of human rights violations [still] happening, including torture, including landmine issues.

Amid the fanfare that accompanied Myanmar president Thein Sein's visit to Australia, Rohingya refugee Mohammed Anwar said: "We are losing more rights, we are suffering more, and we are at the verge of . . . losing our existence." Events in 2017 proved that those concerns were well-founded.

The Rohingya Genocide

Myanmar is home to many minorities who have suffered long-term persecution at the hands of the government, responding sporadically with armed resistance. In late 2016, the Tatmadaw began a campaign of ethnic cleansing against the Rohingya people in Rakhine State, in Myanmar's west. The junta and nationalist Buddhists depict the Muslim Rohingya minority as invading Bengalis who have settled in Rakhine.

Following an attack on police allegedly carried out by Rohingya insurgents, the Tatmadaw unleashed a campaign of violence throughout Rohingya villages in Rakhine State. The International Crisis Group summarized the nature of this campaign, drawing on UN reports:

Widespread, unlawful killings by the security forces and vigilantes, including several massacres; rape and other forms of sexual violence against women and children; the widespread, systematic, pre-planned burning of tens of thousands of Rohingya homes and other structures by the military, BGP (Border Guard Police) and vigilantes across northern Rakhine State.

As they forcibly drove the Rohingya people out of Myanmar, Tatmadaw soldiers were told to "kill all you see, whether children or adults." Associated Press has found evidence of mass graves and bulldozed villages. After a fact-finding mission, UN officials declared that Tatmadaw leaders must face charges for genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes. By 2017, nearly a million exiled Rohingya were living in the world's largest refugee camp in neighboring Bangladesh.

The Tatmadaw claimed that an internal investigation had cleared security forces of any wrongdoing. Other Burmese leaders, including Aung San Suu Kyi, downplayed the severity of the violence. Even when confronted with grisly details of the Tatmadaw's actions in Rakhine at the International Court of Justice in 2019, Suu Kyi still continued to dispute claims of genocidal intent by the military.

A Blind Eye

As these crimes came to light, other nations ended their own military assistance to the Tatmadaw. Amnesty International, among other groups, called on Australia to follow suit. However, the Australian government refused to do so, instead opting to impose limited sanctions.

John Blaxland defended the assistance program by arguing that Australia could play the role of "honest broker" in the crisis. He claimed that Australia's continued support for the Tatmadaw was the only available avenue to influence change. Phil Robertson, deputy Asia director of Human Rights Watch, took a scathing view of this response, calling it a "total abandonment of human rights" and "literally whistling past the graveyard."

Yadanar Maung, a spokesperson for Justice For Myanmar, was also appalled by Australia's continued involvement:

It is shocking that Australia is collaborating with military training facilities and seemingly condoning their approach to law, while there is extensive evidence that the graduates go on to commit atrocities. . . . Instead of colluding with perpetrators of genocide, we call on Australia to recognize that genocide took place, join proceedings at the International Court of Justice, and sanction the Myanmar military and their businesses.

Meanwhile, in response to a ruling by Papua New Guinea's supreme court, the Australian Border Force has been clearing the Manus Island detention center — which is on Papua New Guinea territory — of asylum seekers. Shockingly, the Australian government offered Rohingya refugees on the island A$25,000 to return to Myanmar, where they will face certain persecution.

Late last year, as Myanmar's elections loomed, the appalling conditions for the Rohingya remained unresolved. But so far as Australian business leaders were concerned, the Rohingya genocide was merely a setback. John Lamb of the Australian company Myanmar Metals was clearly anxious to continue extracting Myanmar's immense reserves of zinc, lead, and silver. He blandly described the situation of the Rohingya as a "terrible tragedy" and an "enormous setback":

The world's reaction was entirely justified, and I think a lesson has been learnt. I hope we won't see it again and I don't think we will.

Lamb's confidence was sadly unwarranted.

The February Coup

In the wake of February's coup, as crackdowns on protestors escalated, the Australian government finally ended military assistance and called on the Tatmadaw to respect the Burmese people's right to assembly and expression. Further action was not forthcoming, even as Australia's allies imposed stronger measures. For example, Australia has not placed sanctions on coup leader General Min Aung Hlaing.

Monique Skidmore, an expert on Myanmar, has characterized the Australian response to the Tatmadaw's actions as "very soft." Green and Labor MPs have called for sanctions and for the government to grant asylum to students from Myanmar who are in Australia, as well as to those fleeing repression. So far, the government has only committed to a parliamentary review of sanctions.

Sanctions are a deeply flawed instrument of international relations. Nevertheless, the Australian government's hesitation about deploying such a commonly used tool is telling. Australia's ruling class is far more interested in economic and political stability than economic and political freedom for the people of Myanmar.

With significant private investment at stake, and heightened rivalries between Australia and China in the region, Australian policymakers are very reluctant to take any steps that may threaten the balance of power in Myanmar. As the Australian Financial Review has reported, the government privately worries that further sanctions may push the junta closer to China, while investors fear that escalating civil disobedience will cause threats to foreign businesses.

In contrast, Australia's Burmese community has led spirited solidarity demonstrations and chalked up some victories. For example, Woodside Energy — which came under fire for its involvement in Myanmar — has committed to withdrawing its workers from offshore drilling sites. However, the company has so far refused to make a firm commitment to make its return contingent on the Tatmadaw relinquishing power.

The Australian labor movement could also help pressure Myanmar's ruling class, as it did in similar situations in the past, by organizing solidarity actions targeting firms that are involved in Myanmar, or by obstructing the travel of key leaders and executives.

The Tatmadaw's crackdown on Myanmar's nascent democracy may have unleashed popular forces with the potential transform the country in a much more radical way than seemed possible before. There are also exciting signs of cooperation between the democracy movements in Myanmar, Thailand, and Hong Kong.

While all of this is going on, we should not expect to see Australia's rulers express any meaningful solidarity with the movement beyond tepid calls for an end to violence — let alone lend it material aid. For Australian capitalism, keeping Myanmar open for business is far more important than supporting democracy and human rights.

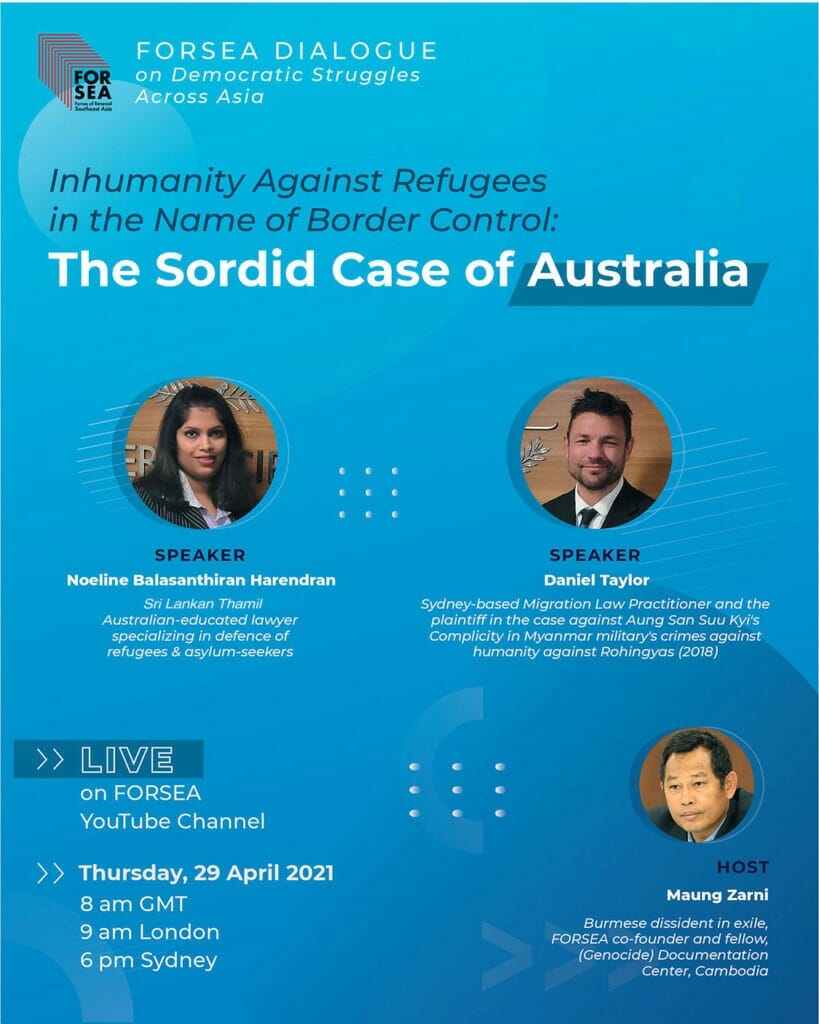

Against this backdrop, Canberra had pioneered a system of offshore processing refuge-seekers in cash-strapped South Pacific island countries such as Papua New Guinea (PNG) and Nauru, with the help of private global security companies such as G4S and homegrown Aussie companies (for instance, CANSTRUCT).

Against this backdrop, Canberra had pioneered a system of offshore processing refuge-seekers in cash-strapped South Pacific island countries such as Papua New Guinea (PNG) and Nauru, with the help of private global security companies such as G4S and homegrown Aussie companies (for instance, CANSTRUCT).